GAME OF THORNS

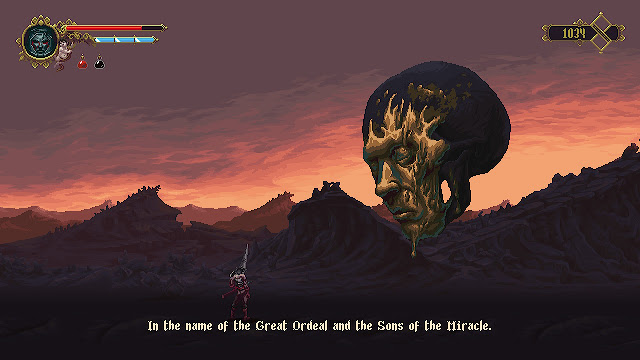

I first stumbled upon Blasphemous through a handful of screenshots years ago. One in particular stuck with me: a grotesque boss depiction, both evocative and deeply unsettling—a blindfolded, blood-weeping infant of colossal proportions, hoisted aloft by a tangle of tree roots, tearing the arms from the hero’s body. Like an illustration from a forbidden folk tale, it disturbed me just enough to make me want to know more.

Now, having played and finished Blasphemous, I can safely say that the title chosen by the Spanish studio The Game Kitchen is spot on. You will curse—often. This is a 2D Metroidvania steeped in Dark Souls-inspired worldbuilding, progression, and narrative ambiguity. It is haunting, punishing, and unapologetically cruel, and I love it for how tightly its difficulty is woven into its themes of sin, guilt, and penance. It is also profoundly unholy. If you’re looking for body horror, Blasphemous does not hold back.

When I finished the game, I jotted down a few notes—reminders of just how much this experience resonated with me:

A challenging sidescrolling Metroidvania drenched in religious imagery, set in the dark fantasy world of Cvstodia—a land of monsters, suffering, gore, and sharp objects. It is also brimming with pixelated beauty, using multilayered parallax scrolling to present evocative environments in the distance. Snowy peaks, poisonous sewers, haunted libraries, bridges spanning endless chasms, sunlit rooftop spires—the world is constantly poised between torment and beauty.

Religion itself holds little interest for me, so I largely disregarded the explicit story and focused instead on the platforming, exploration, and combat. The game delights in slapping you down, mocking you for dying repeatedly, only to reward you generously once you finally overcome a challenge. It constantly teases unreachable ledges, only to hours later grant you the exact ability needed to reach them.

That loop—failure, persistence, reward—is supported by excellent level design. Checkpoints are well-spaced, shortcuts cleverly integrated, and enemy variety imaginative throughout. Across the roughly 28 hours I spent with the game, it consistently introduced new ideas or reframed old spaces in meaningful ways. I was often compelled to revisit earlier locations with fresh thoughts: What if I offered this relic at that altar I passed hours ago? More often than not, it worked—unlocking obscure secrets, new traversal options, or fragments of lore.

Combat is primarily melee-focused, with a handful of unlockable ranged attacks. Defensive options include a dodge, a parry, and a counter (which I never fully mastered). Every enemy can be approached in multiple ways. Using Tears of Atonement—this game’s experience currency—you unlock additional techniques such as plunge attacks or charged strikes. They’re powerful, but in the heat of combat it’s hard to abandon the reliable standard combos.

The boss battles are the game’s crowning achievement. They are imposing, terrifying, visually inventive, and thematically aligned with Cvstodia’s twisted theology. Every encounter felt fresh and intimidating. It often took a few attempts just to understand what I was facing before I could even begin to fight properly. While rosary beads and prayers can provide modest advantages, victory ultimately comes down to patience, pattern recognition, and execution.

Visually and tonally, Blasphemous stands apart. Its aesthetic recalls the more mature 16-bit platformers of the 1990s, suggesting a vast, half-glimpsed truth beyond the screen. Exploration is rewarded: secret passages open up entirely new regions filled with danger and treasure. The game draws heavily from Spanish folklore, religious art, and the grim legacy of the Inquisition, grounding its fantasy in cultural specificity.

That said, the game flirts with obscurity a bit too much toward the end. Dialogue is stiff, storytelling scattered, and the archaic font does the player no favors. I avoided walkthroughs, but in hindsight they might have spared me hours of unnecessary backtracking. Fortunately, the world is compact enough that unexplored paths remain easy to spot, and fast travel exists in limited but welcome form.

The story unfolds in Cvstodia, a land cursed by “The Miracle,” a divine affliction that warps its inhabitants into grotesque embodiments of suffering. You rise from a heap of corpses as the Penitent One, a silent warrior clad in a conical helmet and armed with a thorned blade. Your task is to confront the force behind the Miracle, ascend a mountain of ash, and seek absolution.

Control-wise, the Penitent One feels excellent. His movements are decisive and immediate, with animations that communicate weight and intent. Defensive tools—dodge, parry, counters—are essential, as is the automatic ledge-grabbing, given how demanding the platforming can be. That same ledge-grabbing, however, occasionally causes frustration when you’re trying to drop down quickly and instead cling back up into danger. Masochism, indeed.

Customization comes via rosary beads, relics, prayers, and sword runes. Many rosary effects felt negligible to me—minor resistances or barely noticeable bonuses. Sword runes offer more dramatic changes, but often at costs I found hard to justify. Prayers, on the other hand, are genuinely powerful and can turn the tide in desperate situations. Health flask upgrades are especially interesting: increasing their potency reduces their number, an irreversible but worthwhile trade-off given how slow they are to use.

There is clearly a wealth of passive storytelling embedded in the game’s visuals and soundtrack. While I appreciate this approach in theory, I admit I’m not particularly adept at decoding it. I tend to absorb the atmosphere and later rely on lore analyses to fill in the gaps. In Blasphemous, however, that deeper lore didn’t grip me. It felt distant, symbolic, and impersonal—more conceptual than emotional.

And yet, that distance doesn’t undermine the experience. The story operates on a higher, more allegorical plane, making it easy to ignore if you choose. The gameplay, while not flawless—some platforming sections overstay their welcome, and a few bosses veer into unfairness—largely works in concert to inspire. You gather fragments, assemble your own understanding, and project meaning onto the journey.

It’s a method of storytelling that echoes how Hidetaka Miyazaki has described his own childhood experiences with stories he couldn’t fully understand. That approach served him well.

It serves Blasphemous well too.

Comments

Post a Comment