RELIVE THE PAST TO RELIEVE THE FUTURE

It’s fascinating to revisit a time when open worlds were still considered experimental. Developers were actively probing the formula—what to include, how to structure it, and how to bind space and narrative together. A spiritual successor to the 3D Prince of Persia games, Ubisoft’s Assassin's Creed presents its world as a playground. The player is encouraged to traverse entire cities to get close to assassination targets, then vanish back into the urban sprawl.

Rather than merely exploring your surroundings, you exploit them. You slip into the mindset of a professional medieval hitman with exceptional parkour skills. Through his eyes, a city becomes a network of interconnected obstacle courses. Crowds serve as camouflage. Buildings become scalable surfaces. And once you reach their highest peaks, you plunge back to street level in spectacular leaps of faith into conveniently placed haystacks.

Unfortunately, Assassin’s Creed is riddled with serious flaws that make it difficult to enjoy—and I’ll get to those—but they never entirely eclipse the brilliance of the core concept. In 2007, this sense of freedom and verticality felt genuinely new. Of course, saying that now borders on the obvious. We know what the franchise would become. As I write this, Assassin's Creed: Valhalla, the twelfth mainline entry, is on the brink of release.

Still, the original Assassin’s Creed was never hailed as a masterpiece—not even at launch. Reviews were mixed, and time has only sharpened its shortcomings. The controls feel erratic. The PS3 version’s abysmal framerate sabotages both movement and combat. The gameplay loop grows tedious far too quickly. Poor audio mixing, combined with a lack of subtitles, makes the story unnecessarily hard to follow—especially for a non-native English speaker.

That’s particularly unfortunate, because the story itself is more nuanced than it first appears. Set in the Middle East in 1191, during the Third Crusade, the game casts you as Altaïr (voiced by Philip Shahbaz), an assassin stripped of rank after violating the tenets of his order and endangering his fellow brethren. To regain his standing, he must carry out a series of assassinations—only to discover that his targets often possess motives more complex, and sometimes more honorable, than expected.

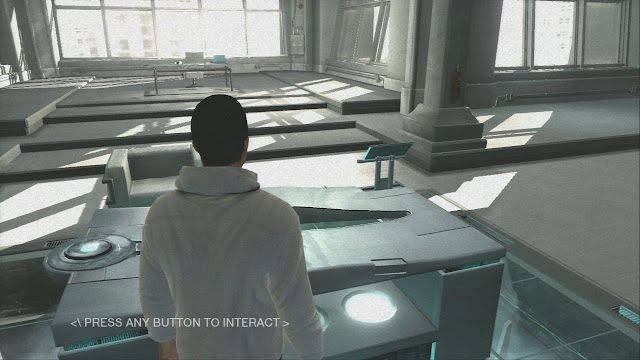

This historical narrative is framed by a modern-day storyline involving Desmond Miles (voiced by Nolan North), a kidnapped bartender forced to relive his ancestors’ genetic memories through a virtual reality device known as the Animus. Both timelines revolve around the eternal conflict between Assassins and Templars, and the claustrophobic modern setting initially makes the historical open world feel all the more liberating.

That feeling doesn’t last.

Before every assassination, you must complete a checklist of investigative tasks—eavesdropping, pickpocketing, interrogating underlings—all of which involve laying low, blending in, and engaging in as little actual gameplay as possible. None of these activities are enjoyable, and the information they provide is rarely useful. They feel like busywork masquerading as preparation.

To make matters worse, I actively dislike Altaïr as a character. His arrogance is grating from the outset, and his redemption arc is telegraphed so clearly it borders on parody. The flat vocal delivery does him no favors. Worse still, his role as a player character is undermined by the game’s most fatal flaw: its controls.

Melee combat depends on precise timing—parries, dodges, chained strikes—but the low framerate introduces input lag that makes responsiveness unreliable. Even basic traversal suffers. Too much is automated, leaving you feeling less like you inhabit Altaïr and more like you’re issuing vague suggestions to a stubborn pet. He often does exactly what you don’t want him to do.

Nowhere is this more evident than during escapes. Run too close to a bench while fleeing guards, and Altaïr may suddenly decide to sit down and blend in. Naturally, this fails when soldiers are already watching you, swords drawn. It’s hard to appear inconspicuous under those circumstances.

I’m ultimately glad Assassin’s Creed became a hit—not because this entry deserves it, but because of what it led to. Freely climbing walls, assassinating unsuspecting guards, and melting into crowds delivers a kind of perverse, almost psychopathic wish fulfillment that I can’t entirely deny enjoying. But this thrill is constantly undercut by repetition, chores, and shallow mission design. The game feels vast yet hollow: the structure is there, but the content rarely justifies it.

It also feels like a missed opportunity to meaningfully explore one of history’s most charged settings. Damascus, Acre, and Jerusalem during the Middle Ages should feel alive, culturally rich, and volatile. Instead, despite their visual detail, the cities feel drained of color and vitality—bled dry, as if Altaïr himself had opened their arteries. It suits his bloodthirsty persona, perhaps, because in Assassin’s Creed, the only things that truly work are climbing and killing.

Comments

Post a Comment