A DEPRESSING RETURN TO PIXEL HUNTING

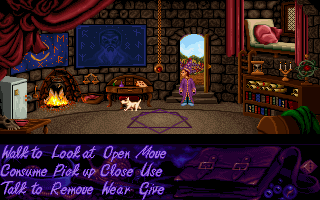

Few things are as soul-crushing as entering a store in a point-and-click adventure. You’re greeted by a screen crammed with tiny, multicolored pixels masquerading as objects on shelves. Most are red herrings. A few are essential. There’s no way to know which is which. This was simply one of the genre’s accepted cruelties back in the day.

As a kid, I loved these screens. They felt like treasure troves—opportunities to expand my inventory with items that might matter later. It was the same thrill as unlocking new abilities in a role-playing game. As an adult, I react very differently. The sight of a hand-painted “Shoppe” sign fills me with dread as I brace myself for minutes of pixel hunting, feeling my remaining lifespan tick away. I don’t have time for this anymore. And judging by the genre’s near extinction, neither does anyone else.

Simon the Sorcerer, developed by British studio Adventuresoft (formerly Horrorsoft), doesn’t merely indulge in this kind of design—it enthusiastically embraces nearly every questionable point-and-click convention of the early ’90s.

From the outset, the world is far too open. You’re dropped into a fantasy land as Simon and immediately given a vague end goal: rescue the wizard Calypso from the evil Sordid. How to accomplish this is anyone’s guess. The map is practically wide open from the start, and even with a fast-travel system, the constant backtracking becomes exhausting. Puzzles are often located far from the items required to solve them, sometimes separated by large stretches of empty space.

Direction is another major issue. There’s little sense of narrative momentum or progression. Sordid doesn’t appear until the very end of the game, and Calypso—the quest giver—is never visually represented at all. You read his letter at the beginning and hear his voice much later, but that’s it. Between those moments lies a long chain of arbitrary puzzles, loosely connected at best. The result is a game that feels aimless, and as a player, you feel equally lost.

Then there’s the pixel hunting. Shops are only the beginning. Crucial items are hidden as tiny details across countless screens, sometimes blending seamlessly into the background. On several occasions, the game requires you to pick up rocks or pebbles from the ground—not any rock, but specific ones that are barely distinguishable from the surrounding scenery. At times even parts of the floor or ceiling turn out to be interactable, with no visual indication whatsoever.

Backtracking is further exacerbated by the sheer number of empty, transitional screens. The world is laid out like a maze, with little sense of geographical continuity. Exiting one screen to the right might land you in the next from the bottom. It’s easy to get lost, and hard to remember how to return to places you actually want to revisit.

Puzzle logic is inconsistent. Some solutions are clever, others tedious or outright arbitrary. To the game’s credit, it often tries to help with visual cues, dialogue hints, and even a wise owl who offers advice when you’re stuck. But when that fails, you’re pushed into the dreaded “try everything on everything” routine—made worse by both the size of the world and your ever-growing inventory.

Certain puzzles require precise timing while a guard or bartender is distracted, and failure forces you to repeat the entire setup. Others are bizarrely strict: why do I need a specimen jar to carry liquid when I already have a perfectly functional bucket? And why must I retrieve one specific skull from a location littered with identical skulls?

Inventory management is another headache. From the very start, you’re encouraged to hoard items “just in case.” Within minutes, your magical hat is overflowing, forcing you to scroll through rows of clutter. Many items are never used, and once they’ve served their purpose they remain as useless debris. There’s no internal logic to what you can carry—my advice is simple: pick up everything, or you won’t get far.

Even in 1994, the interface felt dated. The verb list is unnecessarily long, inflating the already frustrating trial-and-error gameplay. Some commands are used once or twice; at least one (“Close”) seems entirely pointless. Stranger still, the right mouse button goes unused, despite The Secret of Monkey Island having introduced elegant contextual controls four years earlier.

Yet Simon the Sorcerer isn’t irredeemable. Most importantly, it avoids the genre’s most unforgivable sin: unwinnable states. You can’t permanently lock yourself out of progress, and the game ensures you have required items before allowing you to move on. The fast-travel map is also a welcome feature, even if it doesn’t fully mitigate the world’s confusing layout.

Despite the near-absence of a coherent overarching plot, I appreciate the lighthearted tone and occasional dark undertones—particularly the unsettling rock faces as you move eastward. Character animations are expressive and exaggerated, and the exterior backgrounds are often beautiful. Combined with the catchy soundtrack, they suggest a richer world than the gameplay itself allows. Unfortunately, the writing rarely rises above cheap jokes, and the mean-spirited, referential humor rarely lands.

The setting is a chaotic blend of fairy tales and fantasy tropes: echoes of The Three Billy Goats Gruff, Jack and the Beanstalk, Rapunzel, The Hobbit, and more. Witches, bards, dragons, mummies, snowmen, and assorted oddities appear briefly, each guarding yet another puzzle. Comparisons to Terry Pratchett’s Discworld are common, but having never read those books, I can’t weigh in.

While the game clearly aspires to the heights of LucasArts or Sierra adventures, it never reaches them. Structurally and mechanically, it’s closer to King’s Quest (1984). Visually, however, it often looks like a competitor—some backgrounds and musical cues genuinely rival the era’s giants, even if many interiors fall short.

I made it through much of the game on hazy childhood memories alone, but toward the end I encountered sections I’d completely forgotten. Solving them anew was a sobering reminder of just how hostile the game can be to newcomers. I played it on the A500 Mini, where it’s included among 25 titles. At least hard-drive emulation spared me the original Amiga experience of swapping between nine floppy disks.

Comments

Post a Comment